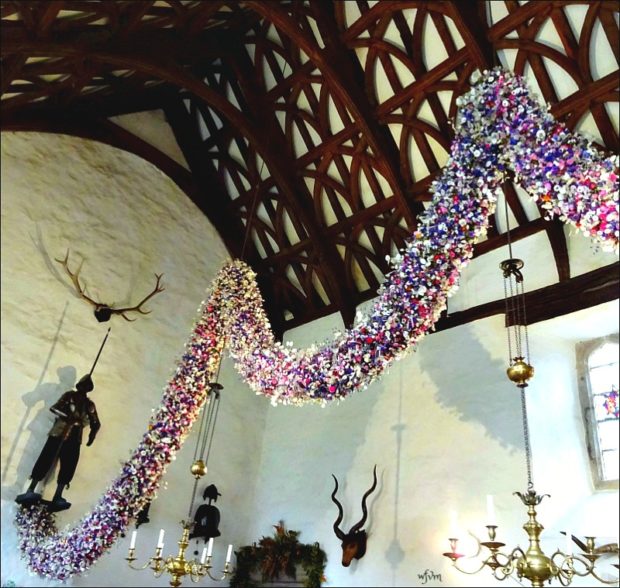

Courtesy of an article in the holiday issue of the British edition of Country Living, I became acquainted with a National Trust property in England known as Cotehele. The property features a rambling stone manor house built in the 14th and 15th centuries, on 1300 acres of property. It is one of the oldest and most well preserved Tudor houses extant in England today. It has been owned and maintained by the National Trust for a very long time. People visit for the gardens, art and tapestries, and events. They support the Cotehele conservation efforts. Country Living visited for the Christmas garland, which has graced the Great Hall from late November through the beginning of January, since 1956.

Courtesy of an article in the holiday issue of the British edition of Country Living, I became acquainted with a National Trust property in England known as Cotehele. The property features a rambling stone manor house built in the 14th and 15th centuries, on 1300 acres of property. It is one of the oldest and most well preserved Tudor houses extant in England today. It has been owned and maintained by the National Trust for a very long time. People visit for the gardens, art and tapestries, and events. They support the Cotehele conservation efforts. Country Living visited for the Christmas garland, which has graced the Great Hall from late November through the beginning of January, since 1956.

The story of the Cotehele garland is an enchanting one. The project takes about a year, start to finish. All of the flowers that go in to the garland are grown at Cotehele. In a good year, 35,000 flowers will be grown and dried especially for the garland. The seed which gets ordered in December will be sprouted, and transplanted into individual planting packs. Grown on until they are sturdy enough to go in the ground, many thousands of seedlings are planted out in April. Both staff gardeners and volunteers help plant, tend, and harvest the flowers.

The story of the Cotehele garland is an enchanting one. The project takes about a year, start to finish. All of the flowers that go in to the garland are grown at Cotehele. In a good year, 35,000 flowers will be grown and dried especially for the garland. The seed which gets ordered in December will be sprouted, and transplanted into individual planting packs. Grown on until they are sturdy enough to go in the ground, many thousands of seedlings are planted out in April. Both staff gardeners and volunteers help plant, tend, and harvest the flowers.

At harvest time, the flowers are cut, and bunched for drying. The flowers are hung upside down in the attic above the kitchen to dry. The varieties of flowers grown are different every year, but the garland is predominantly populated by white flowers. One year the garland was constructed in commemoration of the end of World War 1, and featured red white and blue flowers. The Cotehele garland not only takes months to create, but it is organized around an idea decided upon prior to construction. The garland is not only beautiful, but it is meaningful to the community from whence it comes.

At harvest time, the flowers are cut, and bunched for drying. The flowers are hung upside down in the attic above the kitchen to dry. The varieties of flowers grown are different every year, but the garland is predominantly populated by white flowers. One year the garland was constructed in commemoration of the end of World War 1, and featured red white and blue flowers. The Cotehele garland not only takes months to create, but it is organized around an idea decided upon prior to construction. The garland is not only beautiful, but it is meaningful to the community from whence it comes.

In early November, a team of Cotehele gardeners and volunteers assemble to begin the task of creating the garland. Bunches of pittosporum branches are tied to a stout rope, one bunch at a time, very close together. This creates a green garland some two feet wide and sixty feet long whose branches will capture and hold the flowers as they are stuffed in to the greens. It takes 3 people about a week’s time to transform 40 wheel barrow loads of pittosporum into a 60 foot long garland. Astonishing, this.

In early November, a team of Cotehele gardeners and volunteers assemble to begin the task of creating the garland. Bunches of pittosporum branches are tied to a stout rope, one bunch at a time, very close together. This creates a green garland some two feet wide and sixty feet long whose branches will capture and hold the flowers as they are stuffed in to the greens. It takes 3 people about a week’s time to transform 40 wheel barrow loads of pittosporum into a 60 foot long garland. Astonishing, this.

The garland is hung high in the air space in its green state, and large scaffolding is positioned so volunteers and staff can safely stuff flowers into the greens. The stuffing of the garland with the dried flowers takes lots of hands over the course of 2 weeks. One account says it takes 40 people two weeks to flower up the garland.

The garland is hung high in the air space in its green state, and large scaffolding is positioned so volunteers and staff can safely stuff flowers into the greens. The stuffing of the garland with the dried flowers takes lots of hands over the course of 2 weeks. One account says it takes 40 people two weeks to flower up the garland.

The resulting garland hung in place is magical. In a year in which the dry flowers are especially plentiful, a garland is hung on the jawbones of a whale that has framed the doorway of the great hall since 1837.

The resulting garland hung in place is magical. In a year in which the dry flowers are especially plentiful, a garland is hung on the jawbones of a whale that has framed the doorway of the great hall since 1837.

The story of the holiday garland at Cotehele is a story worth telling. So many people active in the garden for the good of all. This garland is a story about a community, a place, a gardening community, and a sense of purpose. It is a compelling story.

The story of the holiday garland at Cotehele is a story worth telling. So many people active in the garden for the good of all. This garland is a story about a community, a place, a gardening community, and a sense of purpose. It is a compelling story.

This holiday garland makes my heart soar. Any sincere expression of the garden is a source of great joy to me. A community garden such as this at Cotehele is a sure indication of how the love, persistence, and cultivation of a garden can benefit many. I am sure to see it in person is a breathtaking experience.

This holiday garland makes my heart soar. Any sincere expression of the garden is a source of great joy to me. A community garden such as this at Cotehele is a sure indication of how the love, persistence, and cultivation of a garden can benefit many. I am sure to see it in person is a breathtaking experience.

If you are interested in the full story, click on the following link.

https://club.countryliving.com/country-life/deck-the-hall/

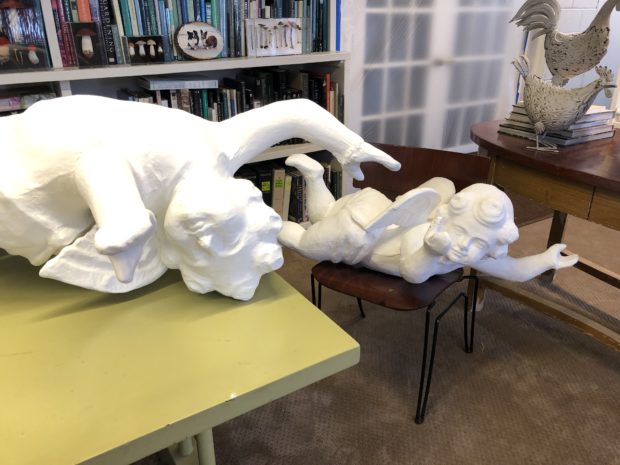

If you are also interested in why I might be talking about a holiday garland on March 11, please read on. The Cotehele garland inspired me to do a version for my newly restored cherubs. See to follow what has occupied my hands over the past two weeks.

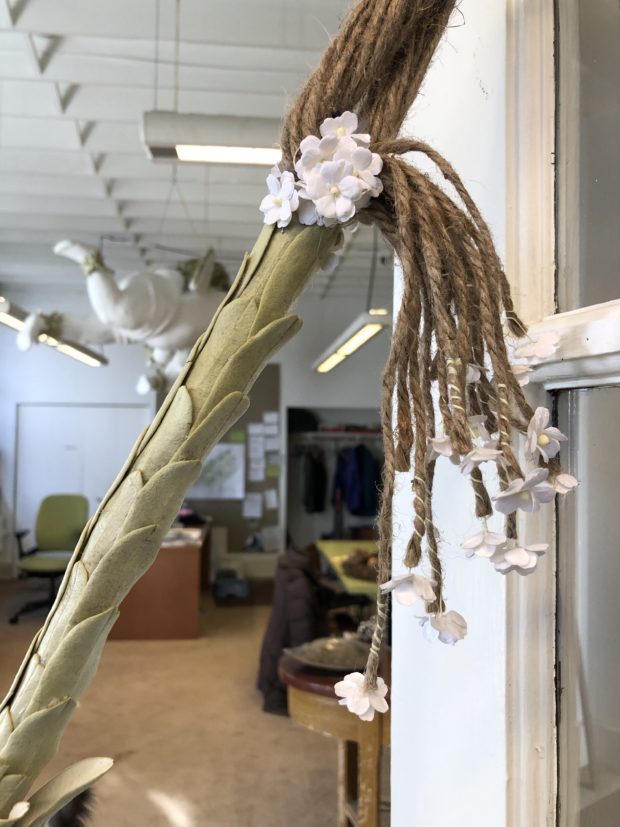

twisted jute rope and dry integrifolia leaves

twisted jute rope and dry integrifolia leaves

I am well on my way to finishing the second garland. How I have enjoyed the magic that is making something.

I am well on my way to finishing the second garland. How I have enjoyed the magic that is making something.