I recently ran across some pictures of holiday containers from the year 2000. The year 2000? I was faint with surprise. It is impossible to believe that we have just finished our 21st season designing, fabricating and installing winter arrangements in pots and containers, but indeed we have. I would have guessed we had 10 years into it, at most. It seems those decades flew by. How is it possible to have sustained a keen interest in the work for that many years, much less kept it fresh and innovative?

Of course one’s approach to the work evolves with experience. In the early days we installed all of the materials in containers on site, in very cold and otherwise inhospitable conditions. All of the materials were inserted into the soil. It took a few years to rewrite that protocol, but now all of the work is done indoors, in custom made forms that are saved and reused from year to year. If you read here regularly, you have heard all about this before. We have a broker of excellent repute and outstanding service supply us with evergreen boughs of incredible size and heft. The picture above and below tell the story of those greens. The dry, preserved and faux materials we are able to add to our arrangements have become more sophisticated and more wide ranging over the years. The materials themselves suggest and inform the design. Great materials enable great work – so all my best to you, and thank you, Rob. But what the 21 years we have in to designing and fabricating the winter pots got me to thinking about has to do with aesthetics. The art and sculpture of it, if you will.

In the beginning we had our mandate – even though we may not have been so conscious of it. Being gardeners, the most beautiful arrangements of greens would of course be those arrangements that most closely replicated the natural arrangement of greens in living and growing evergreen trees and shrubs. Those arrangements engineered by nature have evolved to maximize the health and well being of the plant, and future generations of that plant. Our goal was to arrange cut greens to look as though they were part of a live tree, and growing. We would try to copy nature in exacting detail. There are winter containers we have done that appear to have evergreen shrubs growing in them. We’ve been asked about how to water them more than just a few times. Clients would admire that we were able to make our winter containers look real. Though nature’s works are extraordinarily sculptural, they are after all, nature’s works, and not ours. How would we improve on what nature had already done? We wouldn’t. But we could interpret, celebrate and document our relationship with nature in any number of ways.

Considering the possibility of arranging greens in a not necessarily natural way was uncharted territory. We needed to go in that direction, but that process was like sailing a sailboat directly in to the wind. A sailboat is able to make forward progress into a headwind by a process called tacking. The boat is moved across the wind by turning the bow towards and through the wind in one direction, and then back across the wind in the other. This zig zag movement, if it is skillfully done, has a strong vertical component. It produces forward motion towards a desired destination. If the turning into the wind is of a slight and subtle angle, rather than a sharp 90 degree turn, it produces a phenomena known as sailing close to the wind. Meaning a very small change can make forward progress possible. To anyone reading who truly is a sailor, I apologize for this shallow discussion of tacking. But even a oversimplified version of it helps to explain how our work has evolved creatively.

What are our headwinds? Being reluctant to entertain change is the strongest. Sometimes a lack of imagination or a loss of interest can whip up a stiff headwind. The arrangement pictured above was notable for us, as we deliberately inserted the evergreen boughs adjacent to the centerpiece in a vertical position. It was the first time in at least 15 years – taking that tack. The very first picture in this post illustrates that clearly. The moment we were able to set branches at a horizontal angle in a rigid foam armature, we abandoned ever setting branches vertically again. We were free from the demands imposed by constructing arrangements in the soil. But one set of freedom enabled another kind of prison-not assessing each project on the merits. We made this small incrementally small change in our construction protocol for this pot ostensibly to conceal the faux stems of our faux picks. But the consequences of this small change-the impulse to go vertical in this pot – proved to be substantial. The overall shape was very different-gorgeous to my eye. Natasha did an incredible job setting the greens in this pot. Stunning. Her attention to detail and understanding of mass, volume and shape is obvious.

The following photographs detail the construction of winter arrangements for a set of window boxes that we did last year. It is clear from the pictures that the greens have been set at angles that respond to the geometry of the light ring in the center. The light ring was lined with a heavy weight boxwood garland, that visually connects to the shaped boxwood that follows the radius of the bottom of the light ring. How the boxwood is installed makes the light ring look integral to the arrangement-in a sculptural way. Boxwood would not grow like this, but it might live like this were it trimmed. That would endow the boxwood with the evidence of the human hand. Noble fir branches would not grow like this either. It is clear that this arrangement is of a different sort. And it is definitely not a representation of a noble fir tree.

There are those who might say that the evidence of the human hand is greatly inferior to the hand of nature. I don’t subscribe to that notion, as I do not see the two forces as comparable. They are relatable, integral to one another, but different. Equally interesting. Equally essential.

This picture taken in the shop after the construction was finished illustrates to my mind how a winter arrangement can be sculptural. It took a while to convince Birdie that it would be good and beautiful to install the long greens with an upward trajectory. Like angel wings. What an incredibly beautiful job she did. Ten minutes in, she knew exactly where she was going. Right into the wind.

It was a perfect moment, looking at these sculptures at days end when everyone had gone home. We would install them the following day.

Install them we did.

A client came in last week wearing a tee shirt that had the word BEAUTY printed across it. A few days later her Mom came in, wearing the same shirt. I have no idea as to the origin, intent or meaning of that word having been printed on that shirt. I did not ask. But it did set me to thinking about beauty. And how the pursuit and appreciation of it has been a life’s work, and the source of so much pleasure and satisfaction. Like many others, I came to be a gardener from an intense interest and fascination with the natural world. The visual drama of an emerging leaf, the impossibly intense blue color of a delphinium flower, the fragrance of a mock orange in bloom, the shape of an ancient beech tree-everything about the life of plants provides vigorous exercise and engagement to all of the senses. It is not at all unusual to know of a gardener swooning over this or that flower. So normal in my circle and probably yours. The beauty of nature provides a profound pleasure for the heart, hand, and soul, if you will.

A client came in last week wearing a tee shirt that had the word BEAUTY printed across it. A few days later her Mom came in, wearing the same shirt. I have no idea as to the origin, intent or meaning of that word having been printed on that shirt. I did not ask. But it did set me to thinking about beauty. And how the pursuit and appreciation of it has been a life’s work, and the source of so much pleasure and satisfaction. Like many others, I came to be a gardener from an intense interest and fascination with the natural world. The visual drama of an emerging leaf, the impossibly intense blue color of a delphinium flower, the fragrance of a mock orange in bloom, the shape of an ancient beech tree-everything about the life of plants provides vigorous exercise and engagement to all of the senses. It is not at all unusual to know of a gardener swooning over this or that flower. So normal in my circle and probably yours. The beauty of nature provides a profound pleasure for the heart, hand, and soul, if you will. A definitive explanation of what constitutes beauty is next to impossible, as it does not exist in a vacuum. A beauty designation is entirely arbitrary and fiercely personal. There is a unique relationship between the observer and the observed. What is seen and what is there to be seen. There are those gardeners who adore green flowers or spring ephemera, and those who wax poetic about hot pink peonies, yellow dahlias and red hibiscus. There are others that would be hard pressed to name a plant they don’t like, just as there are those who think that a beautiful landscape would by definition be confined to hellebores and beech trees. Zinnias are most beautiful to me in large part as they remind me of my Mom. Everyone has their own closely held ideas about what is beautiful.

A definitive explanation of what constitutes beauty is next to impossible, as it does not exist in a vacuum. A beauty designation is entirely arbitrary and fiercely personal. There is a unique relationship between the observer and the observed. What is seen and what is there to be seen. There are those gardeners who adore green flowers or spring ephemera, and those who wax poetic about hot pink peonies, yellow dahlias and red hibiscus. There are others that would be hard pressed to name a plant they don’t like, just as there are those who think that a beautiful landscape would by definition be confined to hellebores and beech trees. Zinnias are most beautiful to me in large part as they remind me of my Mom. Everyone has their own closely held ideas about what is beautiful. What constitutes beauty in a garden is a topic of endless discussion. Gardeners and designers of gardens fiercely debate the fine points, and acknowledge their common ground. I admire some gardens and landscapes more than others, as some are more beautiful to me than others. Whether it be plants, houses, landscapes, art, books, music, bridges or… garden pots, a need for beauty has always been an integral part of the human experience. It is as simple and as complex as that.

What constitutes beauty in a garden is a topic of endless discussion. Gardeners and designers of gardens fiercely debate the fine points, and acknowledge their common ground. I admire some gardens and landscapes more than others, as some are more beautiful to me than others. Whether it be plants, houses, landscapes, art, books, music, bridges or… garden pots, a need for beauty has always been an integral part of the human experience. It is as simple and as complex as that. It has been my good fortune over the years to come in contact with ornament for the garden of great beauty. I owe most of that exposure to Rob, who has been shopping and buying for Detroit Garden Works since before it opened in 1996. It is our 25th year in business this year. I find it remarkable that a modestly sized garden shop in the Midwest has not only survived for that long, it has prospered – buying and selling objects and plants of beauty for the garden. That beauty designation by Rob might include something smart and forward thinking. Some other item might be redolent of the earthy odor of history, sassy and off center, or strongly evocative of a farm garden. His is a very discerning eye, and his range of expertise in his field has been amassed over a long period of time. Opening the shop all those years ago was about wanting to share that aesthetic with other gardeners, and make beautiful garden ornament available to others. That is what we do – celebrate the beauty of the garden.

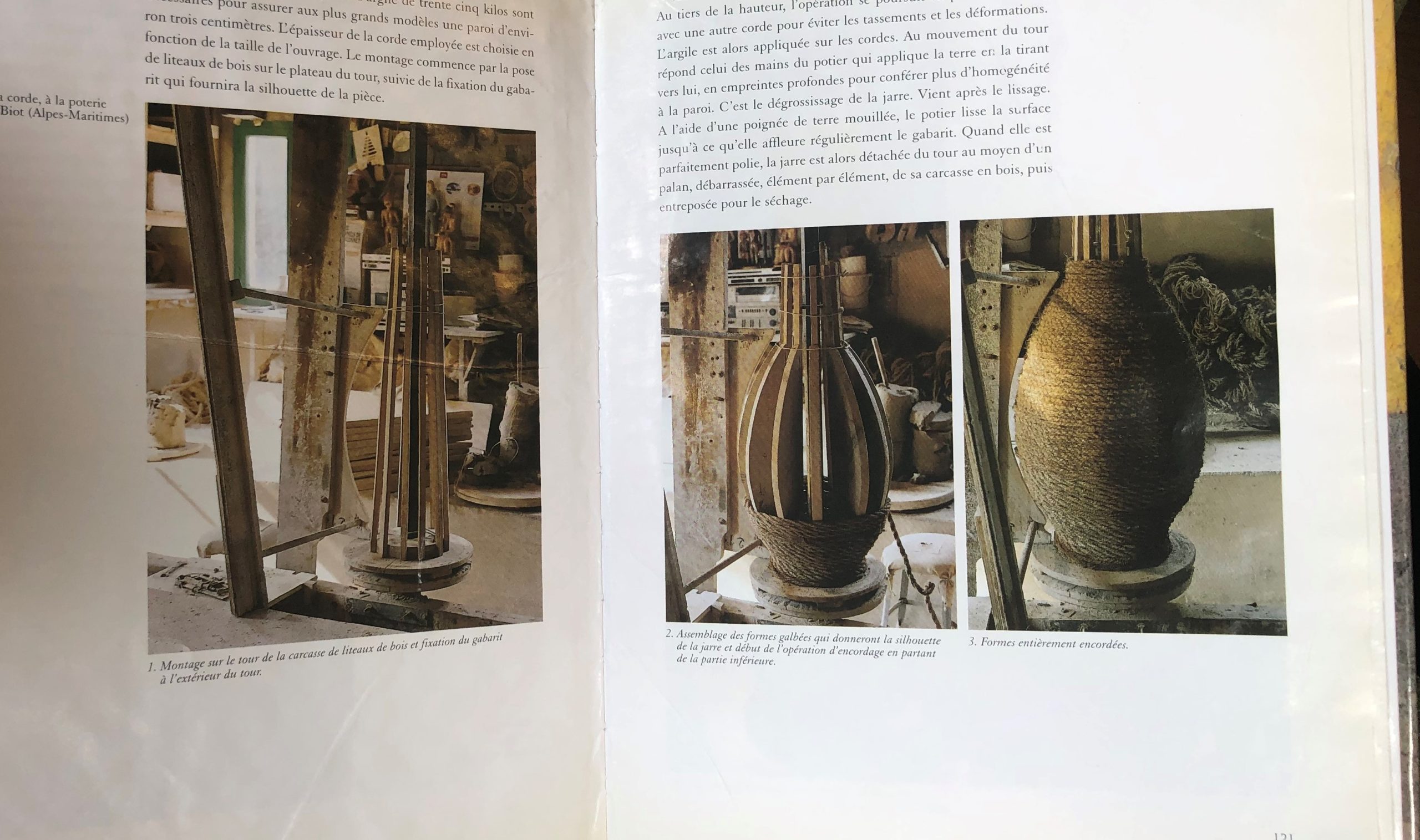

It has been my good fortune over the years to come in contact with ornament for the garden of great beauty. I owe most of that exposure to Rob, who has been shopping and buying for Detroit Garden Works since before it opened in 1996. It is our 25th year in business this year. I find it remarkable that a modestly sized garden shop in the Midwest has not only survived for that long, it has prospered – buying and selling objects and plants of beauty for the garden. That beauty designation by Rob might include something smart and forward thinking. Some other item might be redolent of the earthy odor of history, sassy and off center, or strongly evocative of a farm garden. His is a very discerning eye, and his range of expertise in his field has been amassed over a long period of time. Opening the shop all those years ago was about wanting to share that aesthetic with other gardeners, and make beautiful garden ornament available to others. That is what we do – celebrate the beauty of the garden. Which brings me to a discussion of these pots. They are of French manufacture. A poterie that has been in business since the late nineteenth century has evolved from a company making terra cotta roof and drain tiles to a fine art studio creating pots of great beauty for the garden. The poterie was built but 300 meters from their clay quarry. There is precious little about them that is not to like. The sculptural shapes are classically French. The designs date back centuries. Each pot is hand made, and signed by the artisan who made it.

Which brings me to a discussion of these pots. They are of French manufacture. A poterie that has been in business since the late nineteenth century has evolved from a company making terra cotta roof and drain tiles to a fine art studio creating pots of great beauty for the garden. The poterie was built but 300 meters from their clay quarry. There is precious little about them that is not to like. The sculptural shapes are classically French. The designs date back centuries. Each pot is hand made, and signed by the artisan who made it.

The contrasting surfaces are as appealing to the touch as they are to the eye.

The contrasting surfaces are as appealing to the touch as they are to the eye. This picture makes it clear that each pot is hand made. Each one of these olive jars is subtly different in shape and size than its neighbor.

This picture makes it clear that each pot is hand made. Each one of these olive jars is subtly different in shape and size than its neighbor. The pattern of the rope inside survives the glazing and firing process.

The pattern of the rope inside survives the glazing and firing process. The stamps

The stamps The collection of medium olive jars

The collection of medium olive jars

This is indeed an extraordinarily unusual and beautiful collection of pots.

This is indeed an extraordinarily unusual and beautiful collection of pots.