No discussion of sheep farming would be complete without a big nod to the dogs. A flock of 1100 sheep, living on hundreds of acres of hilly land, would be next to impossible to handle without herding dogs. There comes a time when those sheep have to come in. The ewes are about to have babies. The sheep need to be sheared. The stray sheep from a neighboring farm need to get singled out, and sent home. Farming has its cycles. In and out is simple to write, but much more difficult to accomplish. Farmers who raise livestock need the herding dogs. There are many different breeds of herding dogs, indigenous to many different countries, that make the work of rounding up and watching the livestock possible. Though many of them, including my cardigan corgis, have been bred to herd, a lot of work is involved in training the dogs.

No discussion of sheep farming would be complete without a big nod to the dogs. A flock of 1100 sheep, living on hundreds of acres of hilly land, would be next to impossible to handle without herding dogs. There comes a time when those sheep have to come in. The ewes are about to have babies. The sheep need to be sheared. The stray sheep from a neighboring farm need to get singled out, and sent home. Farming has its cycles. In and out is simple to write, but much more difficult to accomplish. Farmers who raise livestock need the herding dogs. There are many different breeds of herding dogs, indigenous to many different countries, that make the work of rounding up and watching the livestock possible. Though many of them, including my cardigan corgis, have been bred to herd, a lot of work is involved in training the dogs.

The dogs at Easegill Head Farm are farm hands. The work that it took to train these dogs when they were pups is repaid 10 fold, when they grow up, and contribute. They help to make a business – a life’s work – viable.

The dogs at Easegill Head Farm are farm hands. The work that it took to train these dogs when they were pups is repaid 10 fold, when they grow up, and contribute. They help to make a business – a life’s work – viable.

Their accommodations are farm style. Not especially luxurious. I have the feeling that even though they are not house dogs or pets, they are valued members of the family. They perform a service not possible any other way. Having seen Rob’s pictures, I have done some reading about these dogs. They are trained to respond to various verbal commands – lots of them. Up to 30, on this farm. They have incredible, virtually boundless energy. Nothing is right with the world for these dogs unless they are working.

Their accommodations are farm style. Not especially luxurious. I have the feeling that even though they are not house dogs or pets, they are valued members of the family. They perform a service not possible any other way. Having seen Rob’s pictures, I have done some reading about these dogs. They are trained to respond to various verbal commands – lots of them. Up to 30, on this farm. They have incredible, virtually boundless energy. Nothing is right with the world for these dogs unless they are working.

This border collie is staring down a group of sheep. The dogs are very small, in comparison to the sheep. And miniscule in comparison to a flock of sheep. Their ability to learn how to handle a crowd with a look is astonishing. I would not dream of challenging this dog, and neither do the sheep.

This border collie is staring down a group of sheep. The dogs are very small, in comparison to the sheep. And miniscule in comparison to a flock of sheep. Their ability to learn how to handle a crowd with a look is astonishing. I would not dream of challenging this dog, and neither do the sheep.

Others can manage a group all on their own.

Others can manage a group all on their own.

Blue merle Australian shepard herding

Blue merle Australian shepard herding

This breed of dog is known as a Maremma. They protect a flock from harm. They work the night shift, making sure predators do not harm any member of a flock. This Maremma looks cool and calm, but I would guess he would go to the ropes defending his flock.

This breed of dog is known as a Maremma. They protect a flock from harm. They work the night shift, making sure predators do not harm any member of a flock. This Maremma looks cool and calm, but I would guess he would go to the ropes defending his flock.

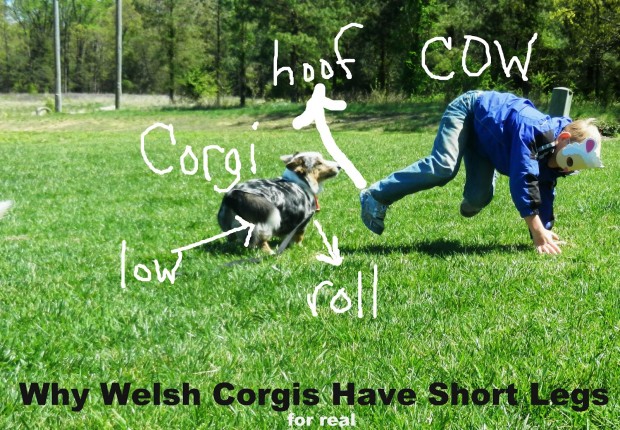

Visitors to Detroit Garden Works are skeptical when I tell them that Cardigan Welsh corgis are herding dogs. How could a dog with such short legs keep up with goats, sheep and cattle?? Milo is actually lightening fast. He can get down the driveway faster than a tennis ball I heave with all my might in a ball launcher. The short legs are a result of natural selection. They nip at the feet of the animals they are herding. A cow that kicks after being nipped would clip a tall legged corgi in the head. I have explained this countless times.

Visitors to Detroit Garden Works are skeptical when I tell them that Cardigan Welsh corgis are herding dogs. How could a dog with such short legs keep up with goats, sheep and cattle?? Milo is actually lightening fast. He can get down the driveway faster than a tennis ball I heave with all my might in a ball launcher. The short legs are a result of natural selection. They nip at the feet of the animals they are herding. A cow that kicks after being nipped would clip a tall legged corgi in the head. I have explained this countless times.

This hilarious drawing tells the tale. Corgis have very short legs for good reason. They are small, and have short legs. They avoid trouble. This does not mean they do not excel as a herding dog.

The herding dogs have my respect. They make a certain kind of farming easier. They are a very important part of the agricultural landscape. A herding dog who can guide a flock to a specified location without alarming or upsetting them is a very valuable asset to a farmer, no matter whether they raise ducks, goats, sheep, or cattle. Good relationships between people and nature have existed for centuries, and take a lot of different forms. Every gardener has a relationship with nature. Spoken, or unspoken. The dogs pictured above make me think about how great gardening is not so much about the spoken language. It is about a bred in the bone need to work. A great love of nature. And a pair of hands looking for work.

The herding dogs have my respect. They make a certain kind of farming easier. They are a very important part of the agricultural landscape. A herding dog who can guide a flock to a specified location without alarming or upsetting them is a very valuable asset to a farmer, no matter whether they raise ducks, goats, sheep, or cattle. Good relationships between people and nature have existed for centuries, and take a lot of different forms. Every gardener has a relationship with nature. Spoken, or unspoken. The dogs pictured above make me think about how great gardening is not so much about the spoken language. It is about a bred in the bone need to work. A great love of nature. And a pair of hands looking for work.

My corgis are not taking the long winter so well. They like a working life. This picture of them sparring-they are not happy with a lack of work. I get this. Our hope is that spring is not far off.

My corgis are not taking the long winter so well. They like a working life. This picture of them sparring-they are not happy with a lack of work. I get this. Our hope is that spring is not far off.